Dispatch #43

All history is historiography.

Know Man Nos My History

The goal of a historian is to construct an account of the world which meets a few criteria:

Accounts for the body of known facts.

Accords with (or elaborates) the social mythology, looking both backwards and forwards.

Fits into a genre of professional activity.

As a craft, modern history has settled into a stance of objectivity, presenting its facts as real reflections or lenses into the past. Where appropriate, the better contemporary historians point out areas of missing data or questionable provenance; such candor reinforces the strength of the remaining edifice. This requires finding contradictions and discerning between them. But this stance of objectivity has become increasingly difficult to maintain—not because historians are less rigorous, but because the conditions of belief have shifted. We live in an age of enlightened false consciousness, in which everyone knows the emperor has no clothes but all agree to admire the tailoring anyway.

Dispatch #39

Classical historiography distinguishes primary sources from secondary sources. This strategy is intended to clarify an epistemology based primarily on documents.

So let’s talk about the composition of history. Recently, a heartwarming story of a library barge trawling the Mississippi broke containment from Facebook onto X. The X user is generally hardened against scams so its traction was middling even tho it was posted from a large real-name real-person account, but a fair number were snookered. The most cursory of investigations reveals that Eleanor Finch, philanthropiste, did not exist until last week. Regardless, the story of the Knowledge Belle will doubtless occupy a corner of some retired school librarian’s heart forevermore.

Nor is the falsification of history unique to the slop factories: one could simply ascribe it to the commons, such as the extensive Zhemao hoaxes, in which a Chinese Wikipedia editor spent a decade creating an elaborate alternate history of medieval Russian-Chinese relations, complete with fabricated sources, fake scholars, and invented diplomatic incidents—over 200 articles totaling 4 million characters, all internally consistent, all completely false, de facto an alternate-history novel. But such ascription would deny the strong normalizing role that folk history and mythology plays in shaping collective memory. Crank historians and AI slop factories are both doing the same work: filling gaps in the record with plausible fictions that serve their purposes.

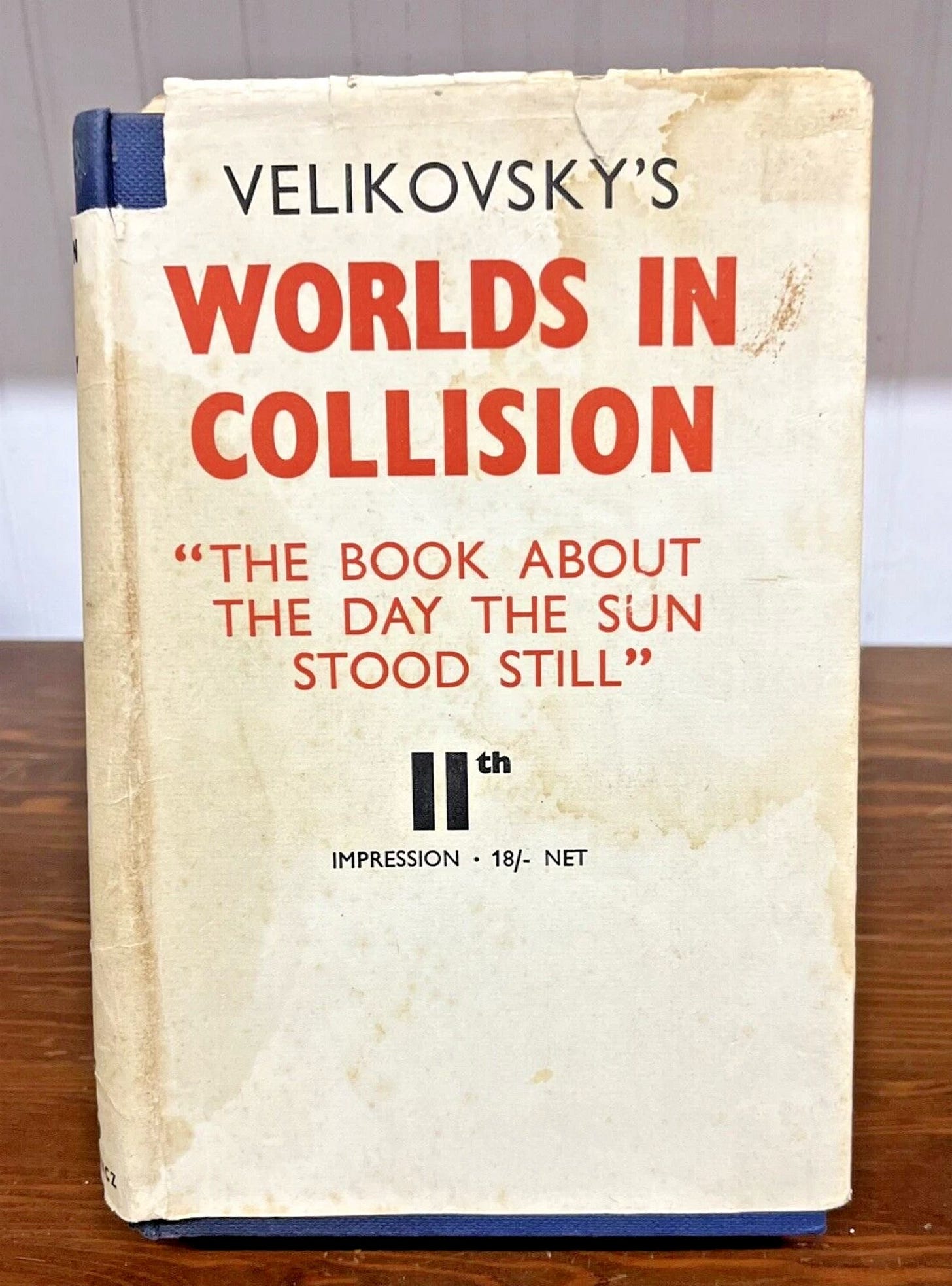

So at the outset we face an interesting question of whether there is a difference between the thoughtless use of knowledge tools in the public record and a rollicking good storyteller who accounts for facts in history, yet is entirely excluded as a crank.

I pick these not because any of them is notable in any way, but because it is not notable. The pool of human knowledge has already become contaminated. And even if you were to build curated data stores—like the White Marble Syndicate project—you still face an onslaught outside the walls.

Meta-Dispatch #2

This nonprofit DAO project is a friend to The Extellıgencer and embodies our strategic approach to memetic sovereignty.

The existence and toleration of slop remind us that the most dangerous lies are the lies we want to believe. Slop is Frankfurtian bullshit:

When an honest man speaks, he says only what he believes to be true; and for the liar, it is correspondingly indispensable that he considers his statements to be false. For the bullshitter, however, all these bets are off: he is neither on the side of the true nor on the side of the false. His eye is not on the facts at all, as the eyes of the honest man and of the liar are, except insofar as they may be pertinent to his interest in getting away with what he says. He does not care whether the things he says describe reality correctly. He just picks them out, or makes them up, to suit his purpose.

And yet, the façade of objectivity is coming down, the barbarians are at the gates, and what’s old is new. Fifteen years ago, we called this “truthiness”; now it has become the reflexive stance of anyone extremely online whether they recognize it or not. (The capacity for such skepticism, in fact, is likely a defining condition of “extremely online”.)

History as an art began with Herodotus and Thucydides, who sought to make accounts of the narratives they had heard and, paralleling Aristotle, to set in order what they observed about the world. Much like astronomy, the narrative has to be constructed out of what can be seen, as slight as that is, and often the field advances by learning to see things that were previously invisible, such as palimpsests underlying vellum manuscripts.

The reigning theory of history today is once again Baconian, conceiving that the collection and collation of a sufficiently large number of facts constitutes a worldview:

Coacervavi omne quod inveni. I have made a heap of everything I have found. Nennius, Historia Brittonum (transcript)

There is no such thing as the past. Or rather, to ascribe “thingness” or “reality” to the past is belied by the question of its (in)accessibility. What we have before us at any moment are a bundle of surviving artifacts, claims about those artifacts, and broadly agreed-upon rules of interpretation. (That is, a historian is someone who practices in the genre of history, to follow Feyerabend.) There is nothing more noumenal, more tantalizingly untouchable, than the moment a thin sliver of a second behind you.

Dispatch #31

This dispatch, in three parts, is an attempt to illuminate the paradigmatic successes and failures of historic truth-seeking paradigms. While rooted in the history and philosophy of science, particularly physics, science as natural philosophy forms an excellent testbed for ideas with the complications of sociological experimentation.

Now, how does this intersect with zero-knowledge proving, institutional intelligence and security, and life in a world of augmented machine intelligence?

Historians have always worked with incomplete artifacts inside of frameworks of interpretation. But all historians, perhaps even the discipline itself, have shared the assumption that there is a single identifiable recoverable past, even if we can only glimpse it distantly.

Now we find among the Akashic records an interesting claim by certain Bitcoin partisans that history itself began with the blockchain. There is a parallel with classical historiography even in the weak case: what we have is a set of artifacts called notes and code, and an agreed-upon set of rules for interpreting these entrails which are presented to us. Nor do we need to be too skeptical: we have before us code and proof of work.

Scott Stornetta co-invented the blockchain at Bell Labs in 1989–1992. He was motivated by the observation that all existing systems require trust in an authority. “Could you build a system that removed that requirement, even if the whole world were involved in collusion?” What if physical reality was the witness instead? He intended the blockchain to be what he called a “reverse panopticon”, through the medium of which even one individual could stand up for the truth. The blockchain was invented to inscribe truth onto the ledger of reality indelibly.

But clearly this is a different kind of history, if that is the right word, than what has gone before. For one thing, it is a future history: one sure way to prove something in the present can be pegged to now is to tie it to a blockchain height protected by an amount of work. The historian calls this a terminus a quo, a point before which a given event could not have taken place under the rules believed to obtain. Proof of work is thus a sort of security budget for history: not strictly insurmountable, as Stornetta sought, but requiring conspiracy against self interest on a scale which would destroy the conditions of sanity.

In “Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius,” Jorge Luis Borges imagined an encyclopedia which simply fabricated its facts in a coherent act of joint worldbuilding, prefiguring the publication of Tolkien and Alan Moore’s Watchmen. Towards the end, the fictionalized alternate history threatens to overturn the real world, presumably less by being an entertainment and more by being a sufficiently moving account to compel conversion on the road to Damascus.

The parallax shift occurs when we realize that all history is Tlönian, or rather, that all history is historiography. Any account is always already an account of itself, of its own making: how and why does it ask you to believe and act? Does it beguile or justify or poison? The stories you tell and are told—and the evidence they account for or omit—structure the meaning of the world.

So blockchain maximalists claim to solve the problem of history by the interesting move of claiming that immutable history began with the blockchain. Bookmark that.

Moving from proof of work to zero-knowledge proof of work, we find a scheme likewise accounting for the world as a heap of notes and locks. The elaboration is that every possible history becomes private: if a ZK proof lock tree only requires the revelation of one branch, then arbitrarily large and complex bodies of data may remain latent in its state. This is mechanistically desirable for preventing data honeypots, or large single points of capture which compromise the quality of human experience. But we can also read it theoretically as that the security budget of particular histories now becomes as complex as cryptography itself, and the dreams of the spymasters like John Dee are realized.

Bitcoin moved monetary policy from politics to protocol, and whether that move is ultimately successful remains to be judged. A zero-knowledge blockchain—and I would be remiss here not to mention that I am involved in developing Nockchain—a zero-knowledge blockchain shunts more than the rate of financial generation to its protocol, but also the conditions of knowledge itself. That is, we move from PoW history as global consensus ledger to ZKPoW history as global consensus hologram, each embedding therein what he desires.

Contra single histories, either from classical historiography or from Bitcoin maximalism, every branch of a ZK proof tree can conceal or reveal arbitrarily complex claims about the world and its history. We have more than private data—we now have private histories.

Every ZK proof is a Tlönian act, creating its own conditions of belief and truthmaking in a concrete sense under a limited battery of tools. Inasmuch as a particular set of facts is concerned, one controls one’s self-revelation in history, one’s participation in the production of artifacts, perhaps interminably deferred through inherited secrets, a dead hand reaching forwards.

But now we have a new problem: the conditions of public history no longer obtain. Every claim becomes Tlönian: it can create its own conditions of authority, which if accepted become witness. A system of claims asks you to accept not just its content but its epistemology.

Consensus reality fragments under conditions of private history. This has already happened, trivially at the Cold War clash of ideologies and again with the more recent “two movies” competition of narratives. But I should not say “of narratives”, but “of metanarratives”.

Institutions, by which we may understand any time two or more humans draw breath together with intent to cooperate, are unconscious mythologers. The utilization of ZK proving is not merely an objective verification system, altho that’s the market narrative, the Trojan horse. Instead the choice to employ ZK proofs participates in an active creation of a new interpretation of records within some shared conception of validity.

With the introduction of proof-of-work history, we moved from ideology as false consciousness to cynicism, knowing something is a fiction but acting as if it is true regardless. Zero-knowledge proof of work history betokens a move from cynicism to what we might call conscious mythology, which is not the naïve belief of the pre-modern, nor the cynical knowingness of the postmodern, but a third position: the deliberate choice to inhabit a mythology while knowing it’s a mythology. The free spirit consciously chooses his mythology and commits to it fully knowing it’s a construction. This is the only tenable successor position when all myths have become visible as myths.

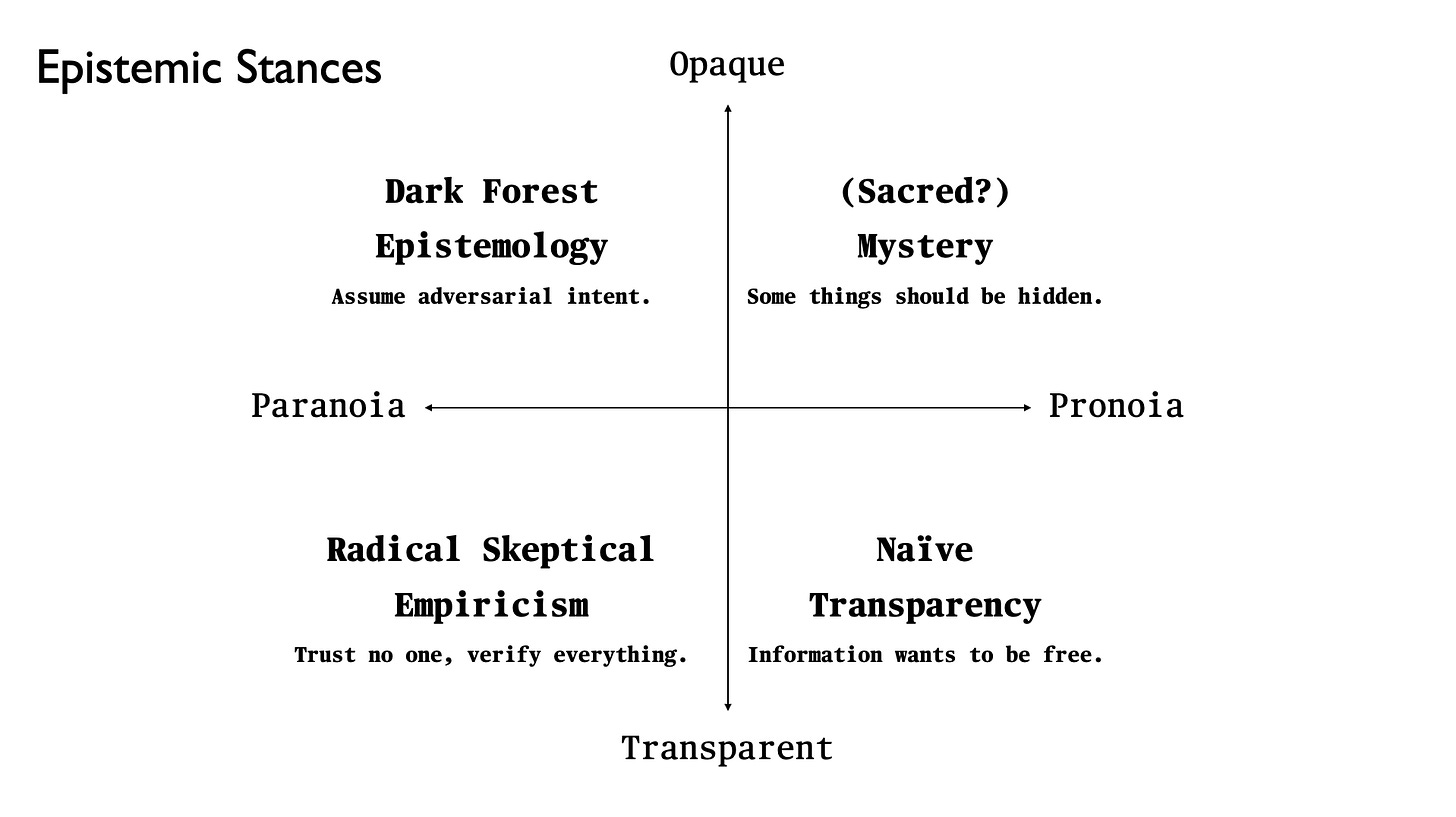

That said, what stance we should have towards a Borgesian metanarrative of history? We here lay out a 2×2 grid, from transparency to opacity and from paranoia (or extreme skepticism) to pronoia (the belief that the world is out to help you).

Pronoid transparency: this is the world of the early Internet. Information wants to be free. It’s susceptible to all sorts of interesting attacks, but essentially it’s a childlike trust because no one has been hurt yet.

Paranoid transparency: the critical assumption made by this level of Humean skepticism is that sufficient information is available, that is, information is not asymmetric. This is fundamentally the public stance of modern enlightenment.

Pronoid opacity: we can call this the quadrant of mystery cults. Secrets protect us, the initiated trust each other, and the Universe through woo moves to protect those who seek its secrets.

Paranoid opacity: AI as adversarial, poison pills, etc. Much of what we have here written.

These are stances, not truths: that is, they are perceived internally as totalizing metanarratives. But they both are motivated by and motivate the utilization of technology; broadly speaking, anyone who believes in one quadrant thinks everyone else is delusional or insane. They are immunological strategies. But generally speaking, the institutions that survive have strong hedges towards paranoia: a cult member may be a pronoiac, but you better believe the cult leader is paranoid. Blockchains move their users leftwards towards paranoia, and artificial intelligence likewise presses upwards towards opacity. If you take both metanarratives seriously, you tend to favor epistemic paranoid opacity. (To reiterate, this is not a value but a stance.)

So which quadrant should we occupy? The answer, perhaps, is that we shouldn’t take any particular stance. Per French critical theorist Jean François Lyotard, postmodernism famously consists of “incredulity towards metanarratives”. He set against them le petit récit or “little narrative” that serves as a loose thread in the warp of a grand mythology.

“Le petit récit” reste la forme par excellence que prend l’invention imaginative et tout d’abord dans la science. The “little narrative” remains the quintessential form of imaginative invention, first of all in science.”

If all history is Tlönian—if records don’t capture reality but only create conditions of belief—then the crucial question isn’t “can we preserve objective truth?” but “how can we build institutions that function as consensus reality fragments?”1 ZK proofs don’t “solve” the truth problem for institutions—they made it legible and thus manipulable. Every proof asks you to accept its epistemology.

Every ZK proof asks you to believe not just its content but its form: “Trust the mathematics, even though the mathematics can hide anything.” Thus the insight about little narratives. In a world of private histories enabled by ZK, we can no longer share one grand metanarrative. Instead, we must cultivate communities of practice—invisible colleges, if you will—each with shared interpretive rules, each knowing that other communities are running entirely different histories. Contra both Stornetta’s dream and the Bitcoin maximalist end-of-history thesis, the blockchain didn’t give us one objective truth. It gave us the substrate for parallel Tlöns, each internally consistent, each presenting boundary conditions for belief on its own terms.

What we have to be wary of, therefore, is letting the mythologies we imagine to be embedded in our tools become totalizing. Large language models and visually generative tools will flood the world with plausible pasts. Blockchains will claim to freeze history immutably. But it is still beyond those protocols, in the place where human agency bears sway, that we face the ancient question with new urgency: does any record actually capture reality, or does it only exercise power to make others believe so? But really, did mythology ever do anything different? And if so, then mythopoesis is the most important activity you can do in an age when all myths are suffocating.

Technology, even augmented machine intelligence and the blockchain do not give us access to an objective singular history. This is why institutional sovereignty matters: not to preserve some objective history, but to have the power to choose which mythology is inhabited, which interpretation rules are followed, and which Tlön is built.

There is an absolutely delightful polysemy in that sentence, which I leave as an exercise to the reader.

It's interesting how this connects to Dispatch #39; that fake library barge story really shows the limits of 'objective' history in our current 'enlightened false consciousness' – briliant!