Dispatch #31

🍃 Natural philosophy and paradigms of truthseeking.

This dispatch, in three parts, is an attempt to illuminate the paradigmatic successes and failures of historic truth-seeking paradigms. While rooted in the history and philosophy of science, particularly physics, science as natural philosophy forms an excellent testbed for ideas with the complications of sociological experimentation.

There are two fundamental types of truthseeking institutions, the religious and the secular. Naturally the boundary between these is porous, but even in the most monolithic societies there is a distinction drawn between the laboratory and the seminary. Here, however, I am less concerned with the institutional or organizational forms of coordination, and instead with the elaboration of paradigmatic and philosophical conditions which must hold to successfully seek truth in its next iteration.

The ultimate goal of natural philosophy is to “save the appearances” Lloyd1978 Barfield1957; that is, to come to an accounting of “why” the world is the way that it is, and not otherwise. The beginning of philosophy is wonder, as Plato has it in the Theaetetus. Mankind looked at the stars, and at the body, and they were struck by the thusness of the cosmos as set over against chaos. The Greek pre-Socratic philosophers rather unsystematically began to account for phenomena in a demythologized sense—that is, they used human reason as the primary tool to account for the brute reality of the cosmos. This is generally considered the departure point for Western philosophy. And while no one will agree on a universal definition, there is a common thread in identifying patterns, causes, and results using certain critical and methodological tools.

At other times he inquires by means of hypothesis, and exhibits certain ways, by the assumption of which the phenomena will be saved. (Simplicius, On Aristotle, Physics)

I identify a few different major paradigmatic frames we can use in considering how truthseeking in natural philosophy has proceeded. There are pieces missing, like the Skeptics, Roger Bacon, Galileo Galilei, and Isaac Newton; to a large extent, engineering and theology are left out although they arguably neighbor this space. I will also state stronger and weaker forms of the styles as I go throughout—the fact remains that each has been superseded for some community of natural philosophers as truthseekers.

To be clear, none of these are complete descriptions of the natural philosophy being carried out at the time, but they are either contemporaneous or post hoc attempts to describe what they perceived to be happening. Furthermore, altho for various historical reasons they are associated with the founder I've identified, it's not always fair to attribute the failure modes of the late decadent school to the founder. (Aristotle is chief among these; he was a careful observer that sometimes got ahead of his skis but in general produced very good work for the data available.)

Aristotelian Natural Philosophy

While the words came to mean other things under the influence of this school, Aristotle was interested in producing a μάθημα, creed/knowledge, via θεωρία, contemplation.

Natural philosophy in the Aristotelian mode relies on careful observation of the natural world combined with logical deduction to explain physical and metaphysical phenomena, emphasizing a holistic understanding of causes and essences. It seeks to uncover universal truths through reasoning from first principles, as exemplified by Aristotle’s works on physics and biology.

Theory of causation

A priori reasoning

Interesting example: Aristotle’s claim that heavier objects fall faster has been derided classically as an a priori deduction from “earth seeks the ground”, a failure of empiricism; the problem with that model is that his model is correct for objects falling in viscous fluid like water.

Failure mode: purely mathematical theories, ungrounded in reality

(A critique of later science, not of Aristotle himself)

This also presages methodological critiques of unfalsifiable theories such as superstring theory and certain formulations of Darwinian evolution by natural selection.

Ptolemaic Astronomy

His laughter at thir quaint Opinions wide

Hereafter, when they come to model Heav’n

And calculate the Starrs, how they will weild

The mightie frame, how build, unbuild, contrive

To save appeerances, how gird the Sphear

With Centric and Eccentric scribl’d o’re,

Cycle and Epicycle, Orb in Orb:

(John Milton, Paradise Lost, Book VIII)

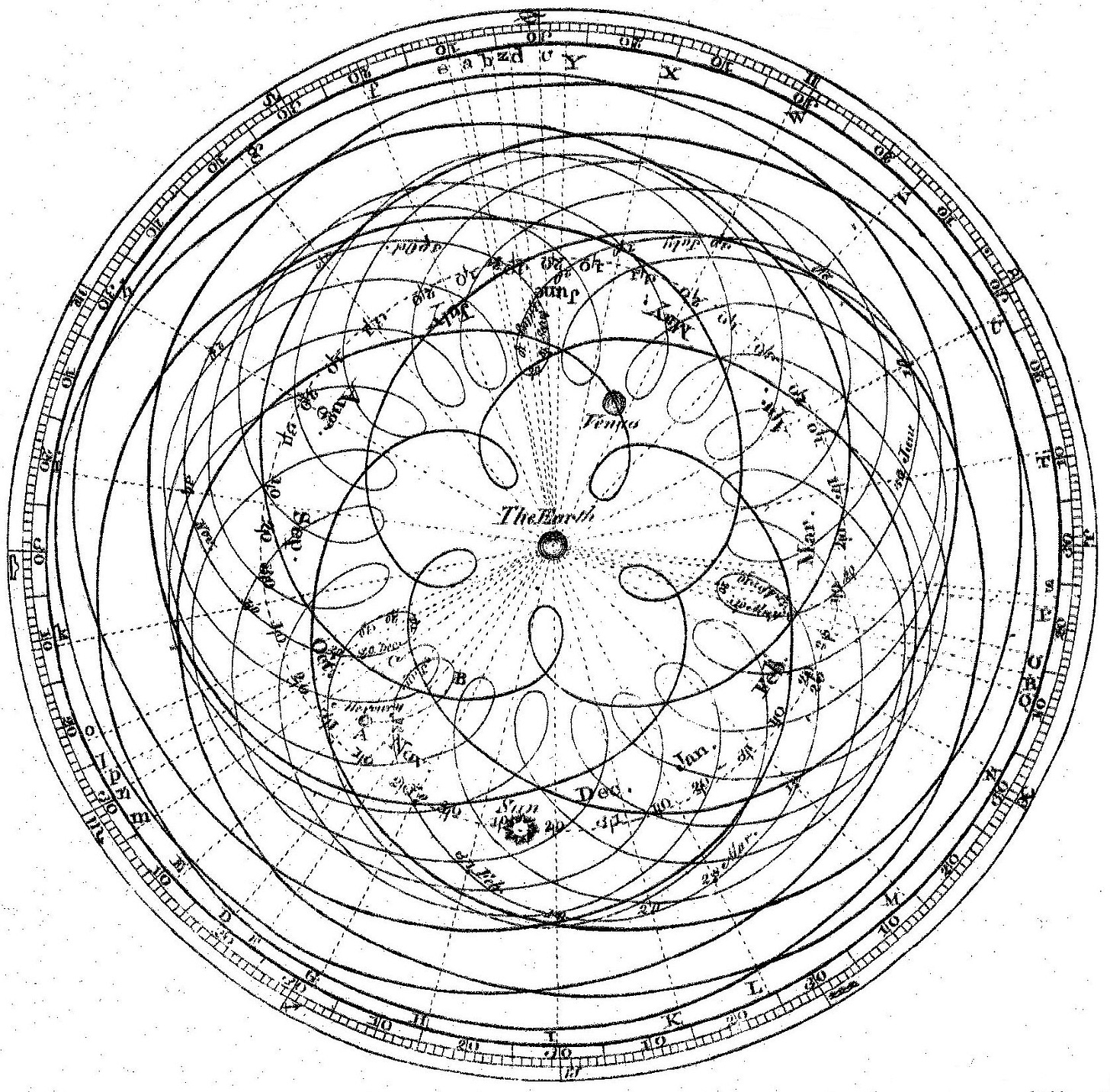

Classical Ptolemaic astronomy accounted for the deviation of the movement of the planets from their crystalline spheres via the expedients of epicycles and eccentrics. An eccentric is a mathematical device to move the center of the perceived circular orbit away from the earth, and an epicycle is a secondary circular orbit around the conceptual point of the planet on its circular orbit.

Classical thinkers, as highlighted by Simplicius in the sixth century A.D., were divided on the physical vs. conceptual reality of the eccentric and epicycle adjustments. Eventually, however, more accurate measurements over longer and longer periods of time led to further correxions via the introduction of “epicycles upon epicycles”, as many later criticized the system as having.

(What do these turn into, in the limit? They are a generalized Fourier expansion of the true orbit (generalized because the functions are not periodic but quasiperiodic and so they do not share the fundamental Kopylov2020).

Ptolemaic astronomy was compatible with Aristotelian cosmology and capable of correctly predicting the movement of the planets for at least a millennium. In what sense was it a failure?

In what sense was this was a methodological failure?

Of course, the Copernican system did not actually solve the problem it was put forward to solve—this is an extremely interesting case study in scientific progress. The Ptolemaic system required 80 epicycles to correctly model the movement of the known planets to the accuracy then possible; the Copernican system required 34, which hardly seems a strong recommendation.

Kepler’s nondogmatic solution of moving to ellipses was, of course, much more correct and saved the appearances with many fewer assumptions, eliminating epicycles entirely.

The failure mode of Ptolemaic astronomy, therefore, was in a sense its capacity to be infinitely elaborated in order to save the appearances. If the canon of parsimony is entia non sunt multiplicanda praeter necessitatem, this was definitely a case in which entia multiplicantur praeter necessitatem.

Baconian Science

Francis Bacon’s approach was rooted in experimental empiricism, prioritizing systematic experimentation and limited inductive reasoning to derive knowledge from sensory data. It aims to build practical, testable understanding through controlled trials, laying the groundwork for the modern scientific method.

Roots of the modern scientific method

Experimentation

Controlled experiments (1753)

Failure mode: Accretive more than theoretical

Bacon was skeptical of grand theories, which he saw as prone to dogma (what he called “idols of the mind”). He pushed for a bottom-up approach: gather data, experiment, and let generalizations emerge slowly. This made his method accretive by design, more a catalogue than a synthesis.

The Fellowship of the Royal Society

The Newtonian paradigm

FRS

The Royal Society formalized with sovereign sanction the existing “Invisible College”, a fraternity devoted to experimental investigation in the Baconian mode. The Invisible College was particularly focused on chemistry and on superseding alchemy in particular, which was obscurantist and unreal in the sense that its physical objective is not possible in this world.

Failure Mode

Back to strictly Baconian science and away from its more bureaucratized mode. The obvious failure mode for Baconian science is that it drinks its own koolaid.

Newtonian Paradigm

Newton's contributions relied on extensive tabulated data collected and sometimes published under essentially Baconian auspices. He was rigorously empirical and experimental. For his work with light and optics, he stated, “hypotheses non fingo”. He prioritized phenomena over cause. Newtonian science encoded certain metaphysical assumptions about absolute coordinate space, for instance, which was carefully considered in an appendix to the Principia Mathematica, and action-at-a-distance, which he rejected on metaphysical grounds even as he followed the math. (Even vociferously empiricist paradigms carry untested and perhaps untestable baggage.)